An Extra (Free) Post: Christ the Image and the Image of Christ

Some thoughts on the most fundamental icon, our encounter with Christ, and centering our senses...

Below is an English translation of a Norwegian article of mine. It’s rudimentary in nature, and therefore perhaps an apt beginning for our future posts. I’m adding it here as a free post, ahead of the next scheduled one on the 15th. I hope you find it useful.

Centering the senses

"At that time Jesus declared, ‘…Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls.’" (Matthew 11, 25, 28-29, RSV)

Most of us feel the need to find "rest for [our] souls.” Circumstances and conditions change, but the basic psychological and spiritual needs of people don’t change. We are still worn out, weary, and weighed down by many things. We can give other, equally relevant words to describe our condition, such as stressed, burned out, empty, or restless. So, to be met and understood by a thoroughly integrated person, one who is manifestly "gentle and lowly of heart," would seem like a wish come true for most of us.

Jesus' contemporaries were directly able to see him, hear him, touch him, and meet him face to face. Imagine if we had lived in that time and place! We can, of course, “travel” in our imaginations and create an inner picture of what it was like to be in the environment around the Master. But the evangelists are realistic in their accounts. They give us to understand that it wasn’t easier to take Jesus' words to heart in their time any more than it is for us today. Experiencing the Savior "live" did not always lead to faith in the listeners.

God's presence

How can we "come to Jesus" two millennia after his ascension? Christians will give different answers to this, depending on which tradition they belong to. Personal prayer, participation in worship, confessions of faith, and the Eucharist are all ways Christians traditionally "come to Jesus.” Similarly, we have the practice of lectio divina (“holy reading”), ruminating on the texts, allowing them to “feed” us and lead us into contemplation.

An interior meeting between God and the human being doesn’t necessarily depend on external action, but it does need our attention. Certainly, a simple, conscious action (such as making the sign of the cross) can sharpen our attention, but attention itself is essentially making ourselves inwardly available to the divine presence through concentration. God is around us on all sides (“in him we live and move and have our being” – Acts 17:28), but for us to realize his presence we have to stop and be present ourselves. In an Irish monastery I once visited, I saw the following inscription: “Bidden or not bidden, God is present.” To establish a meeting between the creator and the creature, both must be present at the same time. God is always there; we, on the other hand, are the ones who more often than not aren’t mentally “present.”

Learning to focus

The Creator took on both the limitations and the potential of human nature when the Second Person of the Trinity – the Logos and Son – became human. In the book On the Incarnation, Athanasius of Alexandria (295–373) wrote: "In his great love, the Savior took on a body and behaved like a human being among humans and met their senses, so to speak, halfway. He himself became an object for the senses so that those who sought God in tangible things could perceive the Father through the works he, the Word of God, did in the flesh." The Savior himself confirmed his divine identity when he said that "whoever has seen me has seen the Father" (John 14, 9). Athanasius wrote that “the Word agreed to appear in a body so that he, as human, could center [human beings’] senses on himself."

For us "centering our senses" means a voluntary narrowing of attention, as when the sound engineer removes background noise to bring out a pure tone, or when the photographer focuses sharply to bring the subject into focus. Everything extraneous must be removed so that the "object for the senses" can emerge clearly.

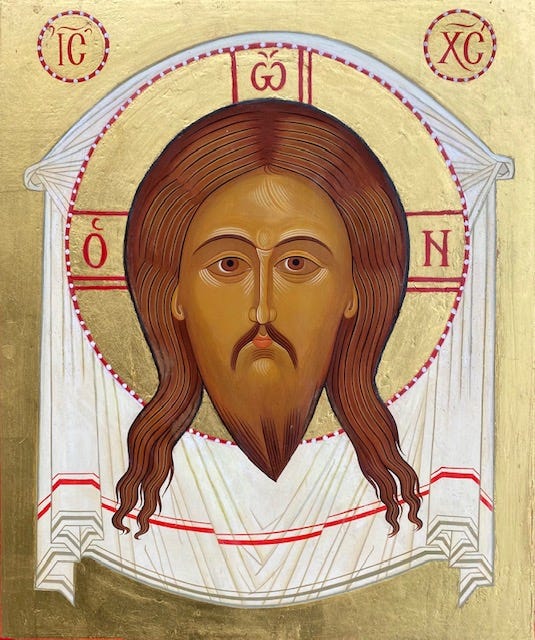

And this is where Christian iconography and the use of artistic images can play a role in “centering our senses” – in this case, the sense of vision – becoming a focus for our attention. In our time, as in past generations, a Christ icon can serve as a mode of focusing our senses on the invisible presence of the Savior who presented himself to humanity — and our material senses — as fully human. While some people “see” Christ with their inner gaze, imaginatively, many people want help to concretize this encounter by gazing upon an icon.

A Christ icon presents a shining face that radiates grace and peace. As a reminder of the Incarnation of Christ, it is the Gospel’s answer to the ancient Aaronic blessing: "The Lord let his face shine upon you and be gracious to you! The Lord lift up his countenance upon you and give you peace!" (Numbers 6, 29), as well as David’s plea in the Psalms: "Thy face, Lord, do I seek. Hide not thy face from me." (Psalm 27, 8–9). It’s a form of communication that, in effect, goes both ways. We believe we are seen by God; now we can “see” in response. The key to this mystery, again, is the Incarnation – that "the Savior took on a body" that could be perceived by the senses, one that could be seen. Implicit in the celebration of the Incarnation is a celebration of the corporeal and material and, by extension, of everything created.

Depictions and reactions

Many people have a photo of a loved one on their desk or in their wallet. This serves as a reminder of someone close to you, a confirmation of love’s bonds, and a tangible comfort. Feelings and memories are brought to life through the image. No one with normal sentiments would say that a photo having emotional value should be taken away or cast aside because it cannot replace the actual person. Expressing such a thought would be unreasonable and offensive.

During the period of Byzantine iconoclasm (726–843) a similar idea was not only expressed but also enshrined in legislation and put into practice. Artistic treasures were lost during this period, treasures that would enrich our knowledge in both ecclesiastical and art history if they could be restored to us by magic. In our own time, we have seen how religious fanaticism and abusive power have affected both living people and living culture. For instance, the tremendous Buddha statues in Afghanistan, blown up by the iconoclastic Taliban regime in 2001, are a shocking example of this.

I recall watching a young man from Saudi Arabia as he told in a television interview how he was encouraged by an Islamist group to get rid of all ties to his family and the past through, among other things, shredding his private photo albums. In his eagerness to achieve the inner freedom he was promised, he did this. In retrospect, he saw the action as the biggest mistake of his life. Suddenly, the past had become like a blank diary and, as a result, his personal identity could be broken down more easily. Many people experience such losses, but for this man, it was particularly heavy because he had inflicted the loss upon himself.

Words and pictures

In the book On the Holy Icons, Theodore the Studite (759–826) continued the work of his predecessor, John of Damascus, in his defense of iconographic art. He was particularly concerned with two sides of the ongoing conflict, namely the relationship between word and image and the relationship between original and copy. He strongly asserted that word and image are in principle equal: "The image [of Christ] was drawn in writing by the apostles and has been maintained until now. The same thing that is depicted there [in the Gospels] with paper and ink, is depicted in the icon with various pigments or another material medium. For the great Basil says, 'Whatever the words in the story convey, the picture in a quiet way shows the same by imitation.’"

Hearing and sight are different senses, but equal as organs of recognition. Here there is no opposition or competition, but rather complementary paths into the human mind. Both the written Word and the painted image convey Christ. At the same time, the Scriptures say that Jesus is both the Word of God and – just as importantly – the Image of God. Athanasius tied these two dimensions together and related them to our salvation when he wrote: "The Word of God came in his own person, because he alone, the Image of the Father, could recreate man made in the same image."

Copy and original

Theodore the Studite also countered the claim that those who used icons confused the copy with the original when they honored an icon or treated it as sacred - as if they believed the wood itself was divine. Such a way of thinking, it was asserted, opened the door to idolatry and, in turn, magic and manipulation. To this, Theodore replied: "Nobody would be so foolish as to think that shadow and truth, nature and art, original and copy, cause and effect have the same essence. [...] Christ is one thing and the image of him is another thing according to nature, even though they have an identity in the use of the same name." An icon of Christ is honored, in other words, because it is an image of God's perfect Image. It is by virtue of this relationship that the icon functions as a channel for God's presence and grace.

When reading the Gospels, we find that the Evangelists depict the same events in Jesus' life in different ways. They present us with variations on a theme. One representation is not for that reason less representative than the other. So too with icons of Christ; different representations give us a richness of nuance and highlight various aspects of the Savior's character. The original is absolute, but the depictions are relative – and yet no less true in what they reflect. Artistically, the difference will be striking if we compare an icon from the Coptic tradition with one, say, of the Russian tradition. When we place before us different iconographic versions of the original, we can see both what is universal and what is particular in our human experience of Christ. He revealed himself in one given historical context, and yet, at the same time, he came to the entire human race for all time. Likewise, he comes to the individual and asks the individual to come to him. “Come to me… and you will find rest for your souls.”

Communication power

Today, in most modern contexts, there is not much danger of icons being used as idols, but rather there is very nearly an opposite problem: a tendency toward reductionism and banalization. We can see this, for example, when a classical iconographic motif becomes just a trendy interior element, or when it is mass-produced as a mediocre souvenir for commercial purposes. There are quite a few ways it can be devalued. This may be due to the fact, paradoxically, that the nature of icon art is conventional and bound to tradition, while at the same time it appears to many to be radical, breaking as it does with trends in contemporary art.

As art has developed in the West, originality, in the sense of the new and previously undone, as well as experimentation and provocation through the breaking of mores and taboos, have become commonplace (and consequently, not so original anymore). Icon art, on the other hand, represents another extreme – one of fidelity to approved prototypes, recognition of the persons and scenes depicted, and an essential contemplative attitude. And it is precisely these values that appeal to many people today, both inside and outside the church. Icons have a strong communication power even outside their own religious context. Even those who aren’t overtly religious or identify as Christians can appreciate the fact that icons point towards the underlying primal image of Christ himself.

We have reached a historical high point in our society when it comes to available distractions. An example might be the run-up to Christmas, with its noise and forced gaiety, which manifests this experience strongly. Pulled and pushed as they are in such hectic times, many of us feel the need for a kind of perceptual asceticism. When the pressures of our busy lives prevail, it becomes necessary to narrow our field of vision so that we might more easily perceive what is essential. We look for God's presence, God’s “appearance.” For this, the icon is one small doorway to this encounter.

By stopping and being silent in front of an icon of Christ, by focusing our eyes and attention on it, we can let ourselves be influenced by the one we behold, and in that encounter, we can have the sort of trusting, nourishing conversation our souls need. “For I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls.” A bonding of two persons who are faithful to each other can become an enduring experience of abiding together, staying continually present to each other. And although it might be difficult to get to that place at first, with practice it can become simpler and increasingly life-enhancing.

Very informative. I’m excited for the future of this sub stack. Where can I get my first icon.

Do you understand why Pantokrator icons do not show the wounds of the crucifixion? It seems like they ought to, given the Scriptural witness and, among others, the reflections of St, Maximus the Confessor. Thank you for any insight or understanding you can share.