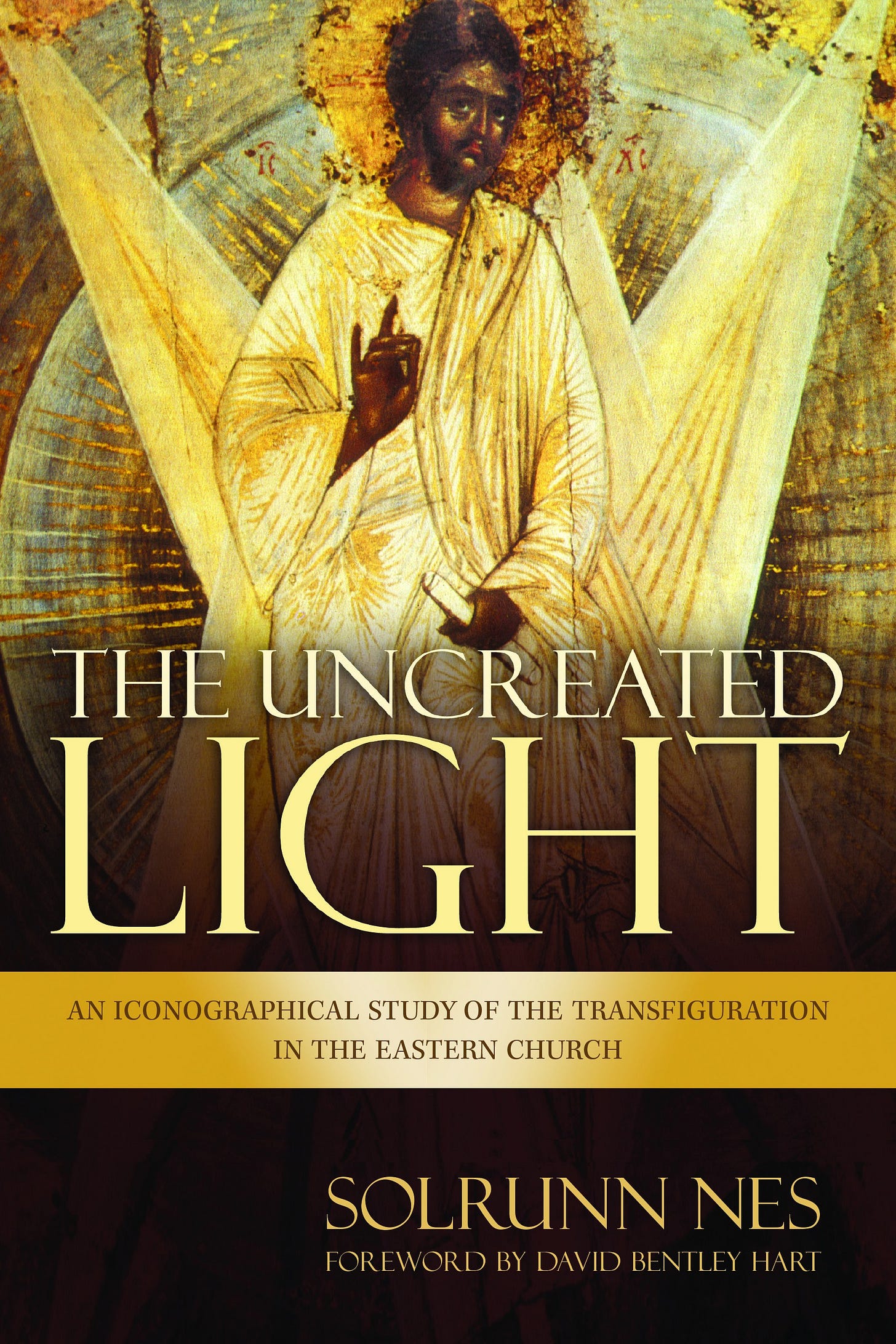

(In 2007 — which seems a very long time ago now — the English translation of my book The Uncreated Light was published by Eerdmans Publishing Company in the United States. At the time David Bentley Hart was not yet my brother-in-law, but already his star was rising as an important theologian and philosopher. Happily, he agreed to supply the Foreword for my book. I hadn’t re-read it in some time, and I had forgotten how fine an introduction it is. Below, I reprint it for those of you who have never read it before — and, if you don’t have a copy of the book itself, perhaps it will inspire you to get one.)

In the icon of Christ’s transfiguration upon Mt. Tabor—as in the feast of light to which it is liturgically attached—the entire “logic” of Eastern Christian theology, devotion, worship, and mysticism is uniquely concentrated. This is not to say that the icon is either aesthetically or doctrinally more important than any number of other canonical Byzantine icons, such as that of the risen Lord liberating souls from Hades, or that of the Crucifixion, or that of the Mother of God with the infant Christ in her arms, and so on; but it is to say that, as an object of contemplation, the Transfiguration image comprises within itself the whole story of creation, incarnation, and salvation in a particular way, with a special harmony of elements, and with a singular intensity. It allows us, in one fixed instant of visionary clarity, to see and to reflect upon the entire mystery of the God-man and of the divinization of our humanity in Him. The light that radiates from the figure of Christ is the eternal glory of His godhead shining through—and entirely pervading—His flesh. It is the visible beauty of the glory that entered the world to tabernacle among us in the Person of the eternal Son: the same glory that passed through the history of Israel, that transfigured the face of Moses, that dwelt in the Temple in Jerusalem, that rested upon the Mercy Seat of the Ark of the Covenant, that overshadowed Mary when the angel of God appeared to her, and that has at various times throughout the history of the Church revealed itself to and in the saints.

The icon also, however, offers us a glimpse of the eschatological horizon of salvation; for the same light that the three disciples were permitted to see break forth from the body of Christ will, in the fullness of time, enter into and transform all of creation, with that glory that the Son had with the Father before the world began (John 17:5), and that the whole of creation awaits with groans of longing and travail (Romans 8: 19-23). Then, to use an image favored by a host of Orthodox spiritual writers, the entire universe will be like the burning bush seen by Moses: radiant with the fire of God’s holiness, but not consumed. And the Christian who prayerfully turns his gaze to the Transfiguration icon, and holds it there, should see himself taken up into the incarnate God, and refashioned after the ancient beauty of the divine image. For, just as it is Christ’s humanity that is transfigured in the light of his divinity, without thereby ceasing to be human, so too our human nature is called to an intimate union with the divine nature; we are created, that we may be deified in Christ. And so the icon is at once a revelation of God made man, and of all of us made god in Him. In it, we see how the kenosis of the eternal Son—His self-outpouring in the poverty and frailty of infancy, manhood, weariness, sorrow, suffering and death—is also simultaneously our plerosis—the filling of our nature with the imperishable splendor of divine beauty and limitless life, the light of rebirth and of resurrection.

In a very profound sense, the entire life of the Christian should be an ascent of Mt. Tabor, a penitent yet joyous approach to the Christ who is Himself the Temple of the Glory, from whom the Shekinah that resided in the Holy of Holies is now shed forth upon all of creation, and into whose presence we are now able to enter without being slain. The icon of the Transfiguration should draw us into an ever deeper contemplation of who Christ is, what light comes with Him into the world, how we are to see and be seen in that light, and how we are to be changed by it. To gaze at the icon in the correct attitude of devotion, and momentarily removed from all profane concerns, is to acquire the proper orientation of our vision, thought, desire, and will: the face of God, the splendor of the Kingdom, the divine destiny that is the vocation of the living soul. The icon of the Transfiguration is one visible aspect of an infinite summons, calling us to a God of inexhaustible goodness, in whom we always live, move, and have our being, and into whom we are meant to venture forever, into an ever greater embrace of His beauty, passing from glory to glory, eternally.

In a sense, every iconographer is always engaged, in some sense, in depicting the Transfiguration, no matter which image he or she is “writing.” Byzantine iconography, as scarcely needs be said, is an extraordinarily stylized form of art, and this is so for a very particular reason: the figures of the icon are not meant to be seen in a natural light, or even in natural perspective. They are, rather, images in which we see the events and persons of scripture and of ecclesial history as, on the one hand, concrete and earthly and, on the other, ethereal and heavenly. The icon is—at least, according to the piety of the Eastern Christian world—a window upon eternity, mediating between the present and the Kingdom that is to come. And, through this window, not only do we look from this world into the Kingdom; our gaze is met by the eyes of another, who looks out from the Kingdom and holds us in his or her gaze in turn (for every icon, according to the theology of the East, is somehow a true “face” of the person it portrays). Every icon, therefore, is already a transfiguration, a dreamlike marriage between the terrestrial and the celestial, and between the temporal and the eternal. The Transfiguration icon itself, therefore, is in a sense the most “transparent” of icons—even, one might suggest, the icon par excellence.

Solrunn Nes is an ideal guide to the iconography of the Transfiguration, in all its dimensions: technical, historical, theological, and aesthetic. She is far more than merely a scholar of the relevant material. She is one of the most accomplished iconographers in the world today; and the icons she produces have few modern rivals, for beauty or for refinement of technique. Her work is, in every significant sense, thoroughly traditional and thoroughly original. Without departing from the canonical rules of Eastern iconography, or from the traditional forms long established for the depiction of Christ and His saints, she nevertheless imbues her work with an extraordinary quality of line and coloration that is entirely her own, and that at times achieves an almost mesmerizing loveliness. (Something of her gifts can be seen—at least, insofar as photographic reproduction allows—in her The Mystical Language of Icons, also published by Eerdmans). This makes The Uncreated Light more, then, than a simple study. Solrunn Nes being herself someone who enjoys a rare and privileged insight into the “art of transfiguration,” so to speak, her book possesses an authority and a completeness of perspective that place it in a very exclusive category. The appearance of this book, in its present edition, is an occasion for rejoicing.

Test