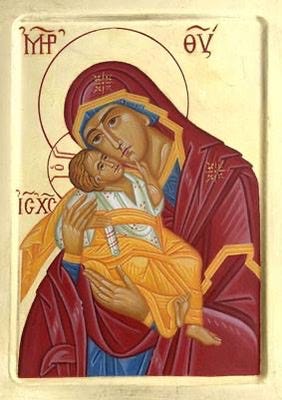

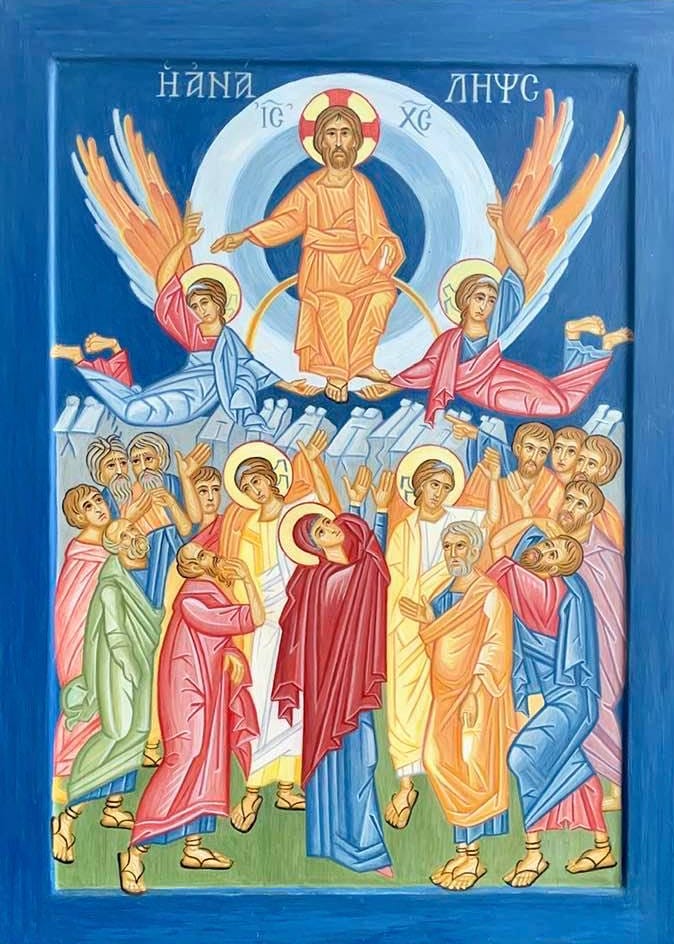

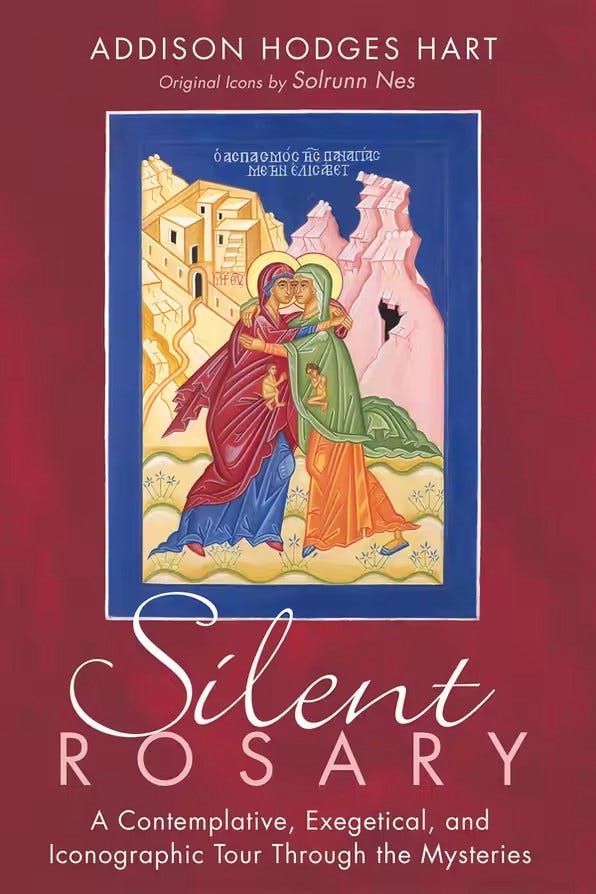

Traditionally, October is dedicated to the Rosary in the Roman Catholic Church. This past year saw the publication of Silent Rosary: A Contemplative, Exegetical, and Iconographic Tour of the Mysteries, a book featuring twenty original icons of mine along with a text by my husband, Addison Hodges Hart. I thought it appropriate to post an excerpt from his text this time around, extracted from the Introduction to the book. I follow this with a link to a series of interviews about the role of Mary in Christian spirituality, which features icons of mine and interviews with both Addison and me among others. Enjoy.

The Significance of Mary (by Addison Hodges Hart)

“Who shall find a valiant woman? Far from the uttermost coasts is the price of her” (Prov. 31:10)… [S]urely we can understand that the valiant woman is the wisdom of God, either Mary, the mother of Wisdom itself, or the Church, mother of the wise, or certainly, the soul as the seat of wisdom. God’s wisdom is called a woman because of the fruitfulness of all good things that flow from her. For it is she who announces: “I am the mother of fair love, and of fear, and of knowledge, and of holy hope” (Sirach 24:24). [1]

In these few lines from a sermon of Adam of Perseigne (c. 1145 – 1221), a Cistercian abbot (and sometime confessor of King Richard the Lionheart), we get a sample of the many connotations that the name and image of Mary possessed from the church’s earliest centuries. Clustered about her was a rich assortment of images – all of them conceptually linked to significant words that were linguistically “feminine” in the original lexicon of the church (Aramaic/Syriac, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin): words such as wisdom, spirit, church, soul, and earth.[2] As “the Woman” and “Virgin Mother” of the Lord, she was from the earliest period viewed as the image and type of these “feminine” associations. She was seen also as the new Eve, “the mother of the living,” and a type of “the virgin daughter of Zion” and the heavenly “Woman clothed with the sun” (see Revelation 12). In short, in Mary early Christians and subsequent generations recognized much more than a simple young woman from Nazareth chosen by God to give birth to Jesus. She was, from the church’s beginnings, an increasingly multivalent figure. In the cited passage above, Adam of Perseign lists three interpretations of “the valiant woman” of Proverbs 31, with whom he clearly associates Mary: “the wisdom of God,” “the church,” and “the soul.”

These three associations are interrelated, as Adam’s sermon suggests. First, Mary was an image or icon of the church – representative of the whole community of God’s people. The roots of this image can be traced to the Old Testament’s ascription of “virgin bride” to the holy city, Jerusalem/Zion, and to “her” as the “mother” of God’s children. The Prophetic books use the metaphor repeatedly (e.g., Isa. 49:18-23; 54:1-8; 66:7-14; Jer. 2:1-3; Eze. 16:6-14; Hos. 2:14-20). And the inclusion into the canon of the Song of Solomon was based on the rabbinical view that it was truly and mystically about Israel’s loving bond with Yahweh.

The nuptial metaphor continues right into the New Testament writings to describe the people of God. For example, we find St. Paul reminding the church in Corinth that he had betrothed them “as a chaste virgin to Christ” (2 Cor. 11:2). Elsewhere he describes the mystical “Jerusalem above” as “the mother of us all” (Gal. 4:26); and – combining these two texts – the early church (ekklesia — feminine in gender) understood “herself” precisely as that mystical “Virgin Mother.” The church, it was said, was a “virgin” when it kept the faith inviolate; it was a “mother” in bringing many children to birth from her baptismal womb. We find this nuptial imagery in the Gospels, as well. Jesus had posed the question to those disturbed by the fact that he and his disciples were not fasting at a time when it was expected that they should, “Can the wedding guests fast while the bridegroom is with them? As long as they have the bridegroom with them, they cannot fast” (Mk. 2:19). By “bridegroom” he was indicating himself, and it seems evident that by “bride” he was designating the people of God. In the fourth Gospel, John the Baptist uses the same analogy to explain both his role and that of Jesus, describing himself as “the friend of the bridegroom”: “He who has the bride is the bridegroom; the friend of the bridegroom, who stands and hears him, rejoices greatly at the bridegroom’s voice…” (Jn. 3:29) The “bride” is the betrothed community that will bring many souls to new birth (a theme, of course, that is presented earlier in the same chapter).[3]

Countless texts in patristic and medieval sources compare the “Virgin Mother” church to the “Virgin Mother” Mary. It was simply a given to the early Christian mind that the two were reflective of one another. In the words of Hugo Rahner, “[E]verything that we find in the Gospel about Mary can be understood in a proper biblical sense of the mystery of the Church.”[4] Just as Mary had virginally conceived and given birth to the physical body of Jesus, so the church conceived and gave new birth to the living members of the ecclesiastical “body” of Christ. As I have written elsewhere:

[There is] no clear distinction… between the heavenly Israel/Jerusalem as “mother” of Jesus and the church as the “mother” of Jesus’ disciples. There is only one “mother” and one archetypal “woman.” Because of this long-ingrained idea, Augustine (354 – 430) could write, in a passage about the virgin mother Mary: “[T]he Church is the mother of Christ” [Sermo Denis 25,8]… [5]

[Mary] is thus the preeminent image of the church (the qahal, the ekklesia, the assembly of God’s elect) that began with the “yes” of Abraham (Genesis 12), the church that experienced her betrothal at the foot of Mount Sinai, and had (as Origen put it in his Commentary on the Song of Songs) the Old Testament prophets, culminating with John the Baptist, as “friends of the Bridegroom,” who had prepared her for her marriage to the Incarnate Word. “The wife of Christ” (“the wife of the Lamb” – Rev. 21:9), wherever such a notion is present in ancient Christian literature and imagery, both orthodox and heterodox, is therefore never to be taken literally; from the outset the idea is iconographic in nature only, a metaphor, a spiritual depiction of the loving relationship between Christ and the gathered community.[6]

The other two associations alluded to in the sermon of Adam of Perseigne – “wisdom” and the human “soul” (meaning, in this case, the comprehensive nature of a person, even to one’s least consciously accessible inner depths) – can be taken together, as they relate both to the image of Mary and to each one of us, and by extension to the role of Mary in the mysteries of the rosary. Again, I quote from my earlier book:

Mary was also at times… associated with the Old Testament personification of Wisdom [as was, of course, Christ]. It is the “wise” person [or soul], after all, who receives the implantation of God’s Word, and every Christian is called to be a wise disciple (and thus a true “child” of the virgin mother church). One can see why Origen would mention her in relation to taking in the “wisdom” contained in the Gospel of John: “No one can apprehend the meaning of it except he have lain on Jesus’ breast and received from Jesus Mary to be his mother also.”[7]

… Mary is aptly an image of the “wise soul,” the wise disciple who gives birth to Christ within her. In this way she not only represents the community of faith, but also the faithful member of that community. The twelfth-century Cistercian Father Isaac of Stella, picking up this slim patristic thread, could thus write: “Whatever is said of God’s eternal wisdom itself, can be applied in a wide sense to the Church, in a narrower sense to Mary, and in a particular way to every faithful soul.”[8]

And, with the contemplative nature of the mysteries of the rosary particularly in mind here, the following passage indicates why Mary was from the church’s beginning the symbol par excellence of the wise Christian disciple:

Mary’s wisdom was, of course, plainly visible in the biblical account. She had “kept all these things and pondered them in her heart… his mother kept all these things in her heart” (Luke 2:19, 51). She was, then, an icon of holy wisdom, pondering the mysteries of revelation. It was never lost on the mind of the church, visible in art and devotion throughout the Christian centuries, that Mary had conceived Jesus within her through her willing reception of the Word of God at the Annunciation. “Mary kept the words of Christ in her heart,” wrote Origen, “kept them as a treasure, knowing that the time would come, when all that was hidden within her would be unveiled.”[9] In a lesser way, as many of the Fathers – prominent among them Gregory Nazianzen and Gregory of Nyssa – asserted, Christ is conceived in our souls and so is born within us. Ambrose of Milan could say, for instance: “When the soul then begins to turn to Christ, she is addressed as ‘Mary,’ that is, she receives the name of the woman who bore Christ in her womb: for she has become a soul who in a spiritual sense gives birth to Christ.”[10] In the words of Augustine: “When you look with wonder on what happened to Mary, you must imitate her in the depths of your own souls. Whoever believes with all his heart and is ‘justified by faith’ (Rom. 5:1), he has conceived Christ in the womb; and ‘whenever with the mouth confession is made unto salvation’ (Rom. 10:10), that man has given birth to Christ.”[11], [12]

There can be little doubt, then, that the practice of praying the rosary, with its many repetitions of the Ave Maria, while simultaneously meditating on mysteries drawn from the accounts of Christ’s life in order to “keep them and ponder them” in one’s heart, had this rationale from the start. That the mysteries begin and end with the Virgin Mother alerts us to the fact that her multivalent image is set before our eyes as both the icon of the community of Christ, in which Mary’s generation of Christ is perpetually reflected in the regeneration of his members, and the icon of the contemplative “wise soul,” in whose heart Christ is born and abides.

So, we might say, that what Mary says to the angel, “Behold [idou] the handmaid of the Lord” (Lk. 1:38), she is also saying to us who are attentive to the mysteries of Christ. “Behold” is a particularly important biblical word, and beholding is precisely what we are called to do before all else. As we behold her and the mysteries to which she points us in our silent meditation, we find ourselves looking into the depths of our own souls where, so we are assured, the Spirit of the Lord is at work.

[1] Adam of Perseigne, “Sermon 5, On the Assumption,” translated by Philip O’Mara, Cistercian Studies Quarterly, Vol. 33.2 (1998), p. 152.

[2] See my book, The Woman, the Hour, and the Garden: A Study of Imagery in the Gospel of John (Grand Rapids, 2016), pp. 27 – 39, for a discussion of ”The ’Virgin Mother’ in Christian Typology.” I also recommend the intriguing scholarly speculations of Margaret Barker, which exhibit her thorough knowledge of the Old Testament and OT pseudepigrapha, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the New Testament and NT apocrypha (including the Nag Hammadi texts), patristic writings, and other relevant literature. She has much to say of value regarding ”the Mother of the LORD” in her numerous studies of Temple worship. One can find a list of her books, as well as downloadable papers and other materials, on her website: http://www.margaretbarker.com/index.html.

[3] As an aside, we must not be troubled by the fact that the image of Mary, identified as it was with the church, was fluid enough to encompass both the analogies of Christ’s “bride” and “mother.” This did not bother earlier generations of Christians, who understood well the poetic and spiritual nature of such imagery. Later generations of Christians have all too often – to their detriment – been literalists, whereas earlier generations were comfortable with allegory, multivalent types, and metaphor. They knew that these images pointed to realities otherwise impossible to articulate.

[4] Hugo Rahner, S.J., Our Lady and the Church, trans. Sebastian Bullough, O.P. (Chicago: H. Regnery, 1965; reprint: Bethesda, MD: Zaccheus, 2004), p. 13.

[5] Hart, The Woman, the Hour, and the Garden: A Study of Imagery in the Gospel of John, p. 32.

[6] Hart, The Woman, the Hour, and the Garden, p. 34.

[7] Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John, Bk. I, Ch. 6 (cf. Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 9 [Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1999], p. 300).

[8] Isaac of Stella, Sermo 51, on the Assumption. Cited in Rahner.

[9] Origen, Homily on Luke, 20. Cited in Rahner.

[10] Ambrose of Milan, De Virginitate, 4, 20. Cited in Rahner.

[11] Augustine, Sermo 191, 4. Cited in Rahner.

[12] For the two passages quoted above, see: Hart, The Woman, the Hour, and the Garden, pp. 34 – 37.

*****************

To view the video of interviews mentioned above, click on this sentence.

Silent Rosary is available from the publisher (here), Amazon (here and here), Barnes & Noble (here), and wherever books are sold.