On the Icon of the Assumption/Dormition

One of the great festal icons

On August 15th, the church celebrates the “Assumption” (which means “the taking up”) of Mary in the West and the “Dormition” (which means “the falling asleep” — a euphemism for death) of Mary in the East. Some Anglican and Lutheran calendars refer to the holy day as “Saint Mary the Virgin.” But whether or not the feast day is called the Assumption or the Dormition, both are based on the very old belief that the Virgin Mother was taken up into heaven by her son after her death.

My intention in this post is not to focus so much on the development of that belief in Christianity, but rather on the iconographic representation of it in tradition. And while the Western tradition decisively includes Mary’s physical body in her “taking up,” the East has left the question open and undecided. My interest here is in the iconographic motif, which for centuries was the same in both East and West. It’s important to recall once again that an icon is not a lifelike picture, but a symbolic one; it isn’t a depiction lifted from the pages of history, but a visual meditation rich in spiritual insight.

According to legend, all the apostles came and gathered around Mary’s deathbed when they heard that she was ill. When that’s possible, this is what we should do for the dying. Nobody should die entirely alone. (This is one of the tragedies sometimes played out in hospitals and nursing homes when nurses are overworked and family members do not show up.)

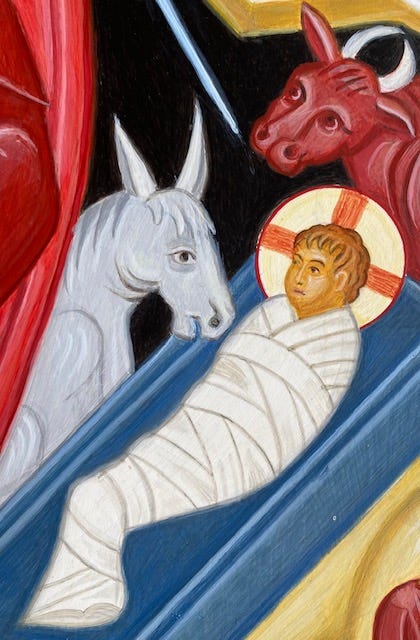

Mary did not die alone. She did not have to cry out, as her Son did in his last hour: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” The icon presented here symbolically shows that her Son comes down from his seat in heaven, embraces his mother’s soul tenderly, and carries her back with him “so that she can always be where he is” (see John 14:3). Strikingly, the roles have now changed between mother and son. As a newborn child, Jesus was carried in his mother’s arms, as depicted in the Nativity icons. In the latter, she is seen holding him and protecting him. But now, at the end of her own life, her Son is holding and protecting her. She is shown wrapped in swaddling clothes, just like the newborn baby in Bethlehem. In the Middle Ages, it was commonplace to depict a soul in this way.

The image of Mary being held by her Son is also a mirrored reflection of the beautiful text by David: “But I have calmed and quieted my soul, as a child quieted at its mother’s breast; like a child that is quieted is my soul. O Israel, hope in the LORD from this time forth and for evermore.” (Psalm 131: 2 - 3, RSV)

This image of the Dormition contains refuge, protection, and warmth. Contemplating the fact that we are all likewise subject to death, the hope that Christ will embrace us at our own earthly end is a great comfort.

An excerpt from our recent book, Silent Rosary: A Contemplative, Exegetical, and Iconographic Tour Through the Mysteries (Cascade Books, 2021). Text by Addison Hodges Hart:

[The Dormition] was originally a commemoration of her death and burial, as well as her entrance into paradise. The mythological story of the event, fleshed out and embroidered in the fifth and sixth centuries, tells of her death and of the miraculous conveying of the apostles from the ends of the earth to her bier. Subsequently, according to one version, upon opening her tomb it was discovered that her body had also been assumed to heaven.

The iconography of the Dormition is particularly touching… Without touching on all the icon’s various details, at the center of it is pictured the apostles, including Paul, gathered about the reposing Virgin. Above this earthly scene we see Christ, bearing in his arms towards the open portals of heaven the tiny, infant-like figure of Mary. She is wrapped in white linen bands, intentionally reminiscent of the swaddling bands in which Mary had wrapped the infant Christ in the cave of the nativity… The motif both mirrors and inverts the image of Mary holding the infant Lord. Here it is she who is the “infant,” newly born into eternal life. Her smallness and her bindings visually heighten the sense of her absolute dependence on Jesus for her Assumption. This feature of her helplessness to rise from death without Christ’s power to free her from it was lost to Western art with the Renaissance…

In this representation, therefore, we find an emphasis on the concept of grace… She had no power to save herself from the grave and no inherent prestige that had not been given to her by grace. She had to be “assumed” by the divine power of Christ. This icon, then, depicts visually what Christ had said to his hearers: “Truly, truly, I say to you, the hour is coming, and now is, when the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live… I am the resurrection and the life… Let not your hearts be troubled; believe in God, believe also in me… When I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and will take you to myself, that where I am you may be also” (John 5:25; 11:25; 14:1, 3).

Silent Rosary can be ordered directly from the publishers (https://wipfandstock.com/9781725272323/silent-rosary/),

from Amazon (https://www.amazon.com/Silent-Rosary-Addison-Hodges-Hart/dp/1725272318/ref=sr_1_1?crid=HCK54D2RAZQZ&keywords=Silent+Rosary&qid=1660475687&s=books&sprefix=silent+rosary%2Cstripbooks%2C146&sr=1-1)

— or from anywhere where fine books are sold.

This is the last free post. After this — except for the occasional open announcement — posts will be for paid subscribers only. Please do hit that “subscribe” button if you haven’t already. Thank you.

"According to legend, all the apostles came and gathered around Mary’s deathbed when they heard that she was ill. When that’s possible, this is what we should do for the dying. Nobody should die entirely alone. (This is one of the tragedies sometimes played out in hospitals and nursing homes when nurses are overworked and family members do not show up.)"

While each one of us dies alone in one sense, the presence of Christ in the persons of his body, the church, is vastly comforting. One of my great regrets in life is that I was not present at the death of my first spouse. I have gained some consolation in the knowledge that in her death she was surrounded by the great "cloud of witnesses." And even more comforting in is the knowledge that Christ himself was present to and for her. The tradition and iconic representation of the gathered apostles at the dormition is only surpassed by the image of Christ embracing the swaddled Mary just as she embraced him at the nativity.

Thank you for this meditation.

You are my introduction iconography, I’m glad David Heart recommend you. I’ll have to say I have been pleasantly surprised as I have never considered the value of such a thing before. I’m sure my fundamentalist upbringing didn’t help as most anything Catholic including it’s icons were held as negatives and I suppose the icons of the churches even idolatrous. So thank you it is a valuable historical lesson and a spiritually uplifting endeavor.